|

|

|

Hansen's Northwest Native Plant Database |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Whether you call the Amelanchier alnifolia by it's most common name of Serviceberry or one of it's more exotic names such as Saskatoon, Shadbush, Shadblow, Indian Pear, Juneberry or May Cherry, you'll fall in love with this northwest native shrub. Plant some of the extraordinarily fine Amelanchier alnifolia (sometimes available in bare root form) in your landscape this spring for years of enjoyment. It's a fine ornamental with sprightly flowers and delicious fruit. In Canada where it's usually called "Saskatoon Berry," the fruit is so much enjoyed the plant is grown commercially for the fruit. Birds are particularly fond of this native. It is not unusual for a whole flock to alight on a Serviceberry when the fruit is ripe. They have quite a conversation as they noisily enjoy the fine berries, chatting and chirping and singing little trills. You might plant an extra shrub or two so there will be enough fruit to share. You won't want to miss out on a Sarvisberry pie or some jam. Delicious! If you have enough berries, try a batch of homemade wine. Plant Brief: A choice deciduous shrub, Serviceberry reaches 6 10. Serviceberry is extremely hardy, ranging from the Pacific coast to the prairies, USDA zones, 3-10. Found on rocky, dry slopes and well-drained thickets, Serviceberry prefers full sun and, aside from a generous layer of mulch, will require minimal attention. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This handsome shrub has outstanding blue-green foliage, delicate 2 flower clusters and brilliant red and yellow fall color. The pea size, purple fruits make fantastic pies and preserves. They were highly esteemed by Native groups and used to improve the flavor of less desirable berries. Not only humans love these fruit - wildlife of all varieties will come for a taste! Strongly recommended for all native plant gardens. Description: The Amelanchier alnifolia (Serviceberry) may also be known as Saskatoon, Shadbush, Shadblow, Indian Pear, Juneberry or May Cherry. If you're in north country or the Appalachians, you might hear it called the Sarvisberry. Amelanchier canadensis is an eastern version of the a. alnifolia. Both are understory shrubs or trees often found growing in clumps in the wild, they live about 60 years. Each year they announce their presence in the early springtime when the slender pinkish buds turn to white flowers blooming so profusely that the branches are obscured by their feathery petals. The blooms are reminiscent of the witch hazel. Deciduous, ranging in height to 35 feet and up to 20 feet wide, the Serviceberry begins it's annual growth cycle with these flowers even before the leaves sprout in their shades of silver or red which turn to green. The leaves are downy when they are young and similar to those of cherry cultivars. The mature leaf color is dark green or even a slightly blue tint on top, not glossy, and pale on the underside. They are thicker and more firm in texture than the cherry leaves. After the blooms fade, the fruits appear in the latter part of June or early July, hence another of it's common names, the Juneberry. These plentiful red-purple fruit are sweet and juicy, soft in texture and often said to be similar in taste to apples. This is quite natural, as they are a member of the apple family. The fruits are about 15mm diameter with 2 - 5 very small seeds in the pear or apple-like core. They resemble high bush blueberries in size and shape, but they are not related to the blueberry. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

One would think the lovely blooms and delicious fruit would be enough of a gift from these trees, but in autumn the oval or oblong shaped leaves, 2-5 inches long and 1-2 inches wide, turn to wondrous shades of yellow-orange to reddish purple before they fall to carpet the ground beneath. In winter the overall rounded shape of the branches are pleasing to the eye with their gray to black coloration until the new red-brown twigs start the cycle anew come spring. The bark itself is interesting, tightly holding the trunk(s) and branches, it has very distinctive vertical lines. It becomes more scaly as the tree matures. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Habitat and Geographic Range: Found on sloping sides of mountains, moist hillsides, on wide prairies, or along side streams or lakes, the Serviceberry is often seen growing as small trees or shrubs. Thickets of this tree are to be seen almost completely across the depth and breadth of the Americas from the Siskiyous clear north to the Canadian/Alaskan tundra. From Newfoundland to Florida, into Texas and Oklahoma, the Serviceberry is equally at home in New Mexico as it is in New York. USDA Hardiness Zone: 3-10. Serviceberry changes form as the growing conditions dictate, forming only shrubs at the edges of it's normal growth range but growing into it's larger tree form where it finds the space and environment. It likes to follow fence rows and to meander along the edges of woods, and can be found growing peacefully among vine maples, all manner of wild roses and other shrubby plants or small trees. It's companions are often windbreak members or woodland plants. Along the sunny canyons and rocky slopes of the Sierras, it is more creeping in habit instead of it's usual upright shrub form. Medicinal uses by Canadian Native peoples: the bark was steeped into a tea for stomach troubles, the bark and twigs were used as tea for recovery after childbirth, and they were combined with other plants for use as a contraceptive. The tough hard wood proved an excellent material for making arrows, for digging sticks, spear shafts and handles for tools. Saskatoon sticks were used to spread out salmon for drying, and the branches were used to construct shelters. Propagation: Serviceberries are very easy to propagate. Seed is said by some to be the easiest way to obtain new plants, as can be seen by the seedlings that will sprout beneath older trees. You can store the seed but it can be a bit slow to germinate, sometimes taking as long as 18 months. However, the quality of seedling plants cannot be guaranteed. Some will grow true to the parent and some will create a completely new variety. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you decide to go the seed route, you can plant them when fresh and allow them to over-winter in the ground, or you can dry them. Gather the ripe berries and place them in a small bucket of dry, clean sand. Crush them with your hands while you mix them with the sand. Sift the sand/seed mix through fine screen to remove larger pieces of fruit. You can then plant the mixture in rows, aiming for 3 seeds per inch. Germination of seeds planted in this manner will happen in the following spring. Expect a germination rate of less than 50%, and the seedlings will grow about 1 foot per year. Seeds may be the best way to grow a large number of plants, but for the home gardener, we prefer the other methods. Culture: Easily grown, Serviceberries' very favorite soil is a rich loamy mix, but they will grow in just about any kind of soil as long as good drainage is provided.If you are growing them for large fruit, by all means give them compost, plenty of water and lots of sun. But if you want more flavor, try to mimic their native habitat of full sun to partial shade and a moderately dry soil.Drainage is the only critical element when choosing a site for these plants. They are fairly tolerant of lime, and will even do well in heavy clay.They are very cold-hardy (remember, they do grow up to the edge of the Northern tundra!), and can take temperatures to at least -20°c. Some say they will survive at much lower temperatures. No hothouse babies, these. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pests and Diseases: The true native Amelanchier alnifolia rarely experiences any diseases and the birds and other wildlife generally keep them pest-free. Give them a well- drained soil and they should be healthy enough to withstand most problems.While no serious insect or disease problems, but like most shrubs or small trees there are a few things the average grower of Serviceberries should watch for. These methods of management will work equally well with most native plants. Fire blight--If the ends of twigs and branches become brown or black, maybe curling over a little, or if cankers which were developed during the previous season begin to seep a cloudy liquid during the damp spring, you may be seeing fire blight. The cause of this disease is erwinia amylovora, a disease which can make the plant look bad as well as prohibiting new growth. To treat, prune out any affected branches making sure to cut well below the canker when the plant is dormant. If you discover this problem while the plant is actively growing, but at least a foot below the canker. Of course, you will want to cut away suckers and water sprouts before they become large. Rust--This common disease will show as brown to orange spots on the leaves. While merely unsightly on the Serviceberry, these spots will spread their spores to infect any junipers close by. The answer here is not to plant junipers near any shrub or tree that shows a tendency to rust. Historical and Special interest: In his novel, The Heartsong of Charging Elk, a story of a Native American man's life, James Welch writes:

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

It is said that the Amelanchier alnifolia or serviceberry was the most important fruit of indigenous peoples in Idaho. They ate the sweet berries fresh from the trees, and picked large quantities of them to dry for use throughout the year. Resembling raisins in appearance when dried individually, they were used to flavor stews, puddings and vegetable dishes. They were mashed and formed into cakes or thin sheets and used as treats. Pemmican was often made of dried berries, dried meat and fat. The Shoshone are said to have made a bread of sunflower seeds, lambs quarter and serviceberries. Cree people routinely used the berries in their Pemmican to cut the fatty taste. The Cree word for the dark purple berries is mi-sakwato-min, or "tree of many branches berries." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Native peoples gathered and dried the fruit for winter use, either dried whole or cooked to a jam-like form before being dried into what today is known as "fruit leather." They used the juice to soak roots of other plants make them more flavourful and sweeter. Modern taste buds may consider the berries too sweet, but they were prized by early travelers, explorers and miners as a wonderful change to their usual more bland fare. People all over the world truly love the Serviceberry wherever it's grown. The Saskatchewan, Canada city of Saskatoon was named by early settlers because the site had many saskatoon berry bushes, or trees. In Maryland, Ellicott City chose the Serviceberry as it's official tree for their bicentennial-plus-25 celebration. Origin of botanical name, original discovery info, etc.: Although the origin of the name Amelanchier remains unclear, we do have clues about it's meaning. The species name alnifolia means alder-leaved. Since the flowers bloom at the same time that shad travel the coastal streams to spawn, we see the common name of Shadbush or Shadblow evolved naturally. Other folk tales say that the name "serviceberry" came because the plants bloomed at the same time circuit riding preachers traveled through the mountains, conducting their services and the flowers were traditionally collected to decorate the churches. |

Photo credit: Walter Siegmund |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

An Appalachian dialect version is Sarvistree. The Juneberry name began, of course, because the fruit usually begin to ripen in that month. Whatever you call them, Saskatoon, Serviceberry, Sarvisberry or Juneberry, we just call these native berries a most delicious gift from a delightful tree. Uses of Plant: A wonderful landscape plant, the flowers, foliage and bark are attractive year-round. Not invasive, the Serviceberry can be planted without fear in beds with other shrubs or trees or as specimen plants. Very resistant to air pollution, they can be grown with a single trunk or a multiple-trunk grove. They make an excellent windbreak when planted fairly close together so the branches can intertwine to form a living fence. Economically the wood of the Serviceberry is occasionally made into tool handles, but it's most common contribution to humans and wildlife are the delicious berries. Wildlife benefits: Serviceberries are eaten by numerous bird species, including pheasant, grouse, mockingbirds, northern flicker, blue jay, American crow, cardinals, cedar waxwings, towhees, American redstart, gray catbird, American robin, varieties of thrush, Baltimore orioles, and many others. Birds love them when they are fattening up for their fall migration. Squirrels, chipmunks, fox, coyotes, rabbits and deer browse its stems, twigs and buds. The spring pollen and nectar are an important source for bees and other insects. |

Photo credit: Walter Siegmund |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

At the table: Very few people will not enjoy eating the fruits fresh from the trees, but they are equally delightful when cooked, dried or made into wine. A very nice quick and easy desert can be done by combining berries with ice cream or whipped cream. You can mash the berries and add a little sugar if desired to make a delicious sauce for ice cream or pancakes. Jams, jellies, muffins, fruit leather, all these and more can be made from these very palatable berries. Tea or beverage flavorings are other ways they can be used. Although completely different in species, Serviceberries can be substituted freely whenever blueberries are called for. Below are a few recipes especially developed for Serviceberry fruits. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Recipes

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Saskatoon Serviceberry Wine

There are two methods recommended in making this wine. No matter which one you choose, first you must gather the berries. Pick only ripe berries. Wash, de-stem and crush the berries. Method 1: Put in primary with sugar, lemon juice, water, and crushed Campden tablet, stirring well to dissolve sugar. Cover with muslin and put in warm place. Add pectic enzyme after 12 hours and wine yeast and nutrient after additional 12 hours. Stir twice daily for 5 days. Strain through a medium-meshed nylon sieve, pressing lightly to extract juice, returning liquor to primary. Recover primary and wait 24 hours, then siphon off sediment into secondary and fit airlock, adjusting volume to allow 3 inches of space for foaming. Move to cooler place. When vigorous fermentation subsides (10-14 days), top up with water or reserved juice. Ferment additional 2 weeks, then rack into clean secondary. Refit airlock and rack after 30 days. Wait another 30 days, rack again and bottle. This is a very good dry wine, fit to taste after 6 months. Improves with additional aging. Two gallons of berries should make 5 gallons of wine. Method 2: Heat to low boil, reduce heat, and simmer covered for 10 minutes. Fold top berries under, recover and simmer another 10 minutes. Pour into nylon jelly-bag and allow to drip over primary until pulp is cool. Meanwhile dissolve sugar into 3 cups boiling water and allow to cool. Add juice, jelly-bag, juice of 2 lemons, yeast nutrients, and pectic enzyme to primary. Wait at least 10 hours before inoculating with wine yeast. Cover well and set in warm (70-75 degrees F.) place, stirring twice daily. When S.G. drops to 1.040 (about 5 days), gently press jelly-bag to extract clear juice, discarding remaining pulp and seed. Siphon off sediments into secondary, top up, fit airlock, and set in cooler (60-65 degrees F.) place. Rack after 30 days and again after another 30 days. Bottle when clear, racking only if additional sediments have formed. Store in dark place to preserve deep ruby color. May taste after 6 months but improves with age. One and one-half gallons of berries should make 5 gallons of wine. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Serviceberry

Jam

Wash and stem berries, then place into a saucepan and crush. Add water and cook over medium heat for 5 to 6 minutes. Measure pulp and add sugar and return to pan. Place over low heat and cook for a few minutes more or till the sugar dissolves. Bring to a boil and add pectin, then hold boil for 1 full minute. Remove from heat, skim foam, and pour into hot, sterile jelly jars and seal. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Serviceberry Jelly

Stem and wash berries. Place into saucepan and crush a few. Add water. Simmer fruit over low heat for about 10 to 15 minutes. Strain the cooked berries through a jelly bag and recover the juice. Measure juice and place in saucepan with sugar. Mix well and place over a high heat. Bring to a boil and add pectin. Return to boil and hold it for 1 full minute. Skim foam and pour into hot, sterile jelly jars and seal. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Serviceberry

& Black Cherry Jelly

Wash and stem serviceberries. Place into saucepan and crush with a potato masher. Wash and stem cherries, place in a separate pan and crush, but do not break the pits. Combine the pulp of both fruits and add cold water, then cover pan. Place over high heat and bring to a boil. Allow to simmer for 10 minutes, then remove from heat and press mixture through a jelly bag, but do not squeeze. Measure recovered juice and place in saucepan with sugar. Mix thoroughly and cook over medium heat till the sugar has dissolved. Bring to a boil, then add pectin and hold at a boil for 1 full minute. Remove from heat, skim foam, then pour into hot, sterile jelly jars and seal. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spicy Serviceberries

Make a syrup of the sugar, vinegar and water. Place cloves, allspice and cinnamon in a spice bag and add to syrup. Bring to a boil and allow to cook for 10 minutes. Remove from heat and allow to cool. Add berries and heat to simmering. Allow to simmer till berries soften, then remove from heat, cool quickly in the fridge and let stand overnight. Next day, remove spice bag and spoon fruit into hot sterile jars. Reheat the syrup to a boil and pass a sprig of whichever herb you've chosen through the hot syrup until you obtain the flavor and aroma you desire. Pour the syrup over the berries and seal the hot jars. Allow to sit for 30 days before serving to meld the flavors. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Serviceberry

Relish

Wash and stem berries. Place into a deep saucepan and crush with a potato masher. Add spices, water, and vinegar. Bring to a boil and stir constantly. Reduce to low heat and simmer for 10 minutes, keeping pan covered. Remove from heat and recover 4 cups of the mixture. Place in saucepan and add sugar. Mix well. Place over high heat and bring to a boil. Add pectin and mix thoroughly. Bring to a boil for 1 full minute. Skim off foam and allow to sit for 3 to 5 minutes. Spoon or pour into hot, sterile jelly jars and seal. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Photo above left and right, credit: Walter Siegmund |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

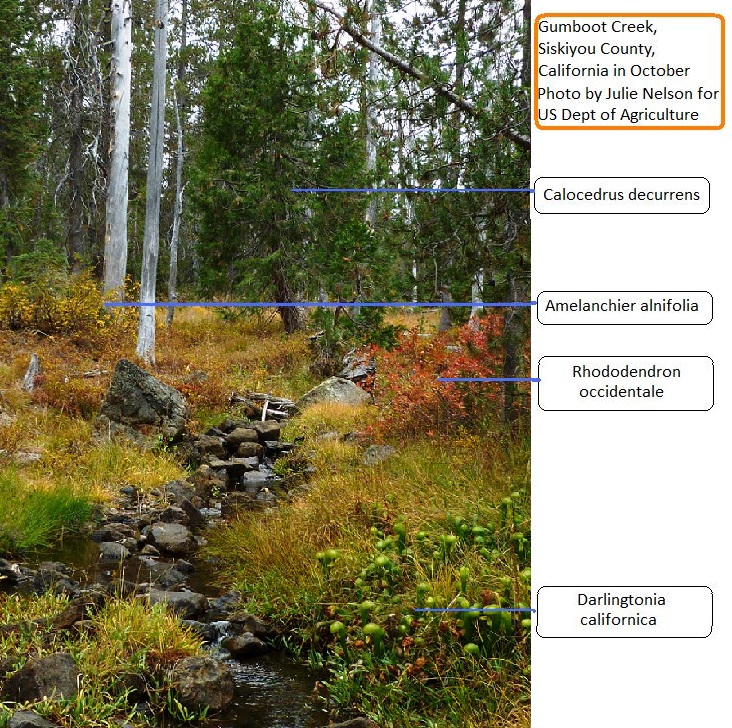

What an edenic scene! The rocks, pieces of trees and shrubs fallen in charming disaray among the colorful fall foliage. Thanks to the astute eye of Julie Nelson, U.S. Department of Agriculture, in this photo we can see the natural, native neighborhood wherein Serviceberry grows in the wild among Calocedrus decurrens (Incense Cedar) and Rhododendron occidentale (Western Azalea). In the foreground is a colony of Darlingtonia californica (Cobra Lily), a rare native of Oregon and northern California. It's preferred habitat are seeps and bogs which are fed by cold running water.

Photo credit: U.S..Department of Agriculture, Gumboot Creek, Siskiyou County |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Photo credit: Walter Siegmund |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Photo, left, credit: Meggaratthe English language; Photo, right, credit: Walter Siegmund |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Photos credit: Walter Siegmund |

Photos We Share!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|