Botanical Discoveries:

Snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus)

Idaho's Bitterroot Mountains,

September 20, 1805

Specimens for

Snowberry (Symphoricarpos

albus) were lost or destroyed during the trip. However the Charleston

Museum has a garden specimen grown from seeds possibly gathered by the

expedition. Specimens were gathered possibly near Pattee Creek, Lehmi Co.,

Idaho, on 13 Aug 1805, or in the Bitterroot Mountains on September 20, 1805.

This Northwest

Native shrub has lovely pink or white bell-shaped flowers and pure white

berries which usually last well through winter and often into spring,

providing food for birds and other wildlife. Beautiful in the landscape. We

especially like it planted with native roses for winter interest. The rose's

red hips and Snowberry's white fruit make a charming combination.

|

|

|

|

The Expedition's Journey

Continues:

A fine morning. Wind from the S.E. At about 11

o'clock the wind shifted to the N.W. We prepare all things ready to

speak to the Indians. Mr. Tabeau and Mr. Gravelines came to breakfast

with us. The chiefs, &c., came from the lower town, but none from the

two upper towns, which are the largest. We continue to delay and wait

for them. At twelve o'clock, dispatched Gravelines to invite them to

come down. We have every reason to believe that a jealousy exists

between the villages for fear of our making the first chief of the lower

village. At one o'clock, the chiefs all assembled, and after some little

ceremony, the council commenced. We informed them what we had told the

others before, i.e., Otos and Sioux. Made three chiefs, one for each

village. Gave them presents. After the council was over, we shot the air

gun, which astonished them much. They then departed, and we rested

secure all night. Those Indians were much astonished at my servant. They

never saw a black man before. All flocked around him and examined him

from top to toe. He carried on the joke and made himself more terrible

than we wished him to do. Those Indians are not fond of spirits- liquor

of any kind.

Captain Clark, 10 October 1804

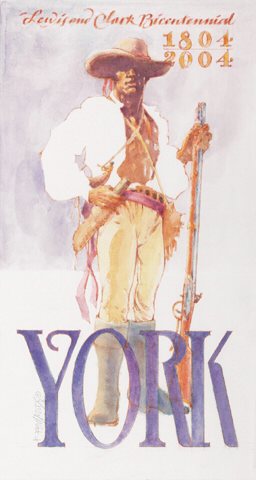

We know the "black man" mentioned here was York, the man

Captain Clark "inherited" as a slave from his father. York and Clark

became lifelong companions though much of this association was as one

human "owning" another.

York was, to the native peoples the expedition met along

the way, the most curious and interesting of the entire traveling group.

Though the expedition included quite a variety of people such as farmers

and frontiersmen from Virginia, fur trappers who were French-Canadian, a

young Indian woman and her baby and even a dog, York was the one person

everyone wanted to see. |

|

Cutting a striking figure, York was very large in stature,

quite strong and his skin was satiny and dark, his hair cropped close to

his head in tight curls. From all accounts, he was said to be a handsome

man with a great deal of dignity tempered with a good sense of humor.

York shared all the duties of the enlisted men and was

often called upon as a showpiece, paraded about and ordered to dance, and

stood while the native peoples "examined him from top to toe." Though this

was undoubtedly humiliating and degrading treatment, York retained his

personal grace and the journaling expedition members noted that he

appeared to enjoy showing his physical abilities to the native visitors.

Though regularly treated as a sort of sideshow (and

In truth, many of the expedition were put on display whenever the native

peoples showed an interest in seeing them), Mr. York was allowed rights

unheard of for an enslaved man. He carried a weapon and was given a vote

on where to establish the winter camp along the Pacific Ocean in 1805.

He repaid these allowances many times over, even risking

his life to save Clark in a flash flood on the Missouri River near Great

Falls in present-day Montana. He hunted and brought in much game for the

larder, saw to pitching the captain's tents, worked the sails and rowed

when needed, in general doing much the same things all the other men in

the expedition did. As the adventure progressed, the travelers forged

themselves into a team, a pioneering family that came together to explore

the continent of North America. However much of a family the expedition became, the fact

remained that York was still a slave. In Lewis's report to Congress, he

listed the members of the Corps who had made the journey to the west and

back, he neglected to mention York. And after the journey was over, York

asked Clark for his freedom as payment for his services on the trip. Clark

refused this request and then complained that York "has got Such a notion

about freedom and emence Services [on the expedition], that I do not

expect he will be of much Service to me again." |

This painting is by Idaho artist, Roy Reynolds. We think it

depicts this outstanding man as he probably was in real life. |

|

York did not take the denial of his request well for he

had a wife in Louisville that he wanted to be with. Instead, he was made

to stay in St. Louis with Clark. In May 1809 Clark wrote that York was

"insolent and sukly, I gave him a Severe trouncing the other Day and he

has much mended."

Eventually, Clark did free York and as severance gave

him wherewithall to start a freight business between Nashville and

Richmond, including a wagon and six horses. It is said that in his later

years, York entertained companions with stories about his adventures with

the expedition—stories that reportedly became taller with each telling. It

is also said he became a heavy drinker which may have been a factor of the

growing yarns. It sounds to us as though he was not unusual in the

socializing and storytelling. As we age, we often remember the past as a

bit more glorious and exciting than we noticed it being the first time

through.

According to letters written by Captain Clark, York died

of cholera sometime between 1822 and 1832 somewhere in Tennessee. He is

likely buried in an unmarked grave. |

Go to our Corps of Discovery Expedition

Bicentennial Index page

to see all links in this series. Or click

here

to go directly to the next installment of our

journey.

|

|

|

Bringing history alive:

Lewis's sketch of the Shoshone peace

pipe from his August 13, 1805 journal entry

CREDIT: Lewis, Meriwether. "Journal

entry for August 13, 1805" Courtesy of American

Philosophical Society, Philadelphia (20). |

|

|

|

Calumet stem peace pipe, Missouri -

possibly collected by Lewis and Clark (from Rivers, Edens,

Empires exhibit) From Library of Congress |

|